This column first ran in The Tablet in January of 2020… Betelgeuse has since made a lovely recovery, thank you!

Like most stargazers, I count Betelgeuse as one of my favorite stars. The name alone (yes, it is pronounced “beetle-juice”) is enough to delight the small child in me. It’s also spectacular to learn about: a red giant star, so puffed out that if our Sun were placed inside it, Earth and even Mars would be orbiting inside the star.

It’s easy to find in January’s skies. Look south for Orion: the three bright stars in a row, his “belt”, enclosed by a box of four bright stars. The most brilliant of those four, Rigel, is at Orion’s left (our right) foot; Betelgeuse is the one at his right shoulder, almost as bright as Rigel, with an unmistakable red color. Both of those are “first magnitude” stars, among the 20 brightest stars to be seen anywhere in the sky. The other two stars of the box (Bellatrix, at his left shoulder, and Saiph, his right foot) are, like the belt stars, only a bit dimmer: “second magnitude” stars.

Except… if you find a clear night this month [January 2020, that was!] and go looking for Orion, you may notice that Betelgeuse is not looking so bright these days. The last time I looked, Betelgeuse was not much brighter than Bellatrix. I am writing this in early January, 2020; who knows how bright it’ll be by the time you read this?

The not so constant sky

From a human perspective, stars are a reassuring constant in an ever turbulent universe, bits of beauty that cannot be touched by our human follies. We might blind ourselves to them, filling our sky with artificial lights and artificial satellites, but the stars themselves stay untouched even as we do our worst.

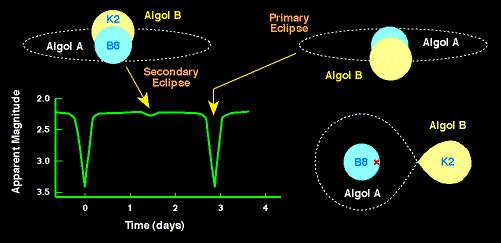

The ancients were aware that certain stars would change their brightnesses. Algol, a second magnitude star in the constellation Perseus, dips to third magnitude for a few hours every three days; it was called a “demon” and the Greeks identified it with the head of Medusa. Mira, a star in the faint constellation Cetus, was given the Latin name for “astonishing”; it varies regularly from second magnitude all the way to tenth magnitude — impossible to see without a telescope — with a period of about a year.

Yet neither star is so bright, or well known, as Betelgeuse. And while both of them may vary, unlike Betelgeuse their variations are at least predictable. (We know now that Algol is periodically obscured by a dimmer companion, and Mira’s physical structure causes it to pulsate.)

In fact, Betelgeuse has also long been known to be a variable; what’s unusual is how much it has dimmed recently. We also know that, given its stellar size and age, Betelgeuse is a candidate to become a supernova in the near future… a possibility that has the Twitterverse excited. When it happens, the star will become as bright as a full moon. Of course, “near future” means anytime in the next 100,000 years.

Changes…

Still, even knowing the physics of this star, it’s still unsettling to see a constellation that I have known since childhood looking very different from what I am used to. Of course you have to know what is normal, before you can appreciate what has changed. And most likely over the next few months we’ll get to see a different change, as Betelgeuse rises up to its previous brightness.

As St. John Henry Newman said — quoted by Pope Francis at his Christmas audience: “Here below to live is to change; and to be perfect is to have changed often.”

Here’s what Sky and Telescope had to say about this as it was happening, and you can find an explanation of what occurred at this NASA site.