NASA’s InSight mission has ended after more than four years of collecting unique science on Mars.

Mission controllers at the agency’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California were unable to contact the lander after two consecutive attempts, leading them to conclude the spacecraft’s solar-powered batteries have run out of energy – a state engineers refer to as “dead bus.”

NASA had previously decided to declare the mission over if the lander missed two communication attempts. The agency will continue to listen for a signal from the lander, just in case, but hearing from it at this point is considered unlikely. The last time InSight communicated with Earth was Dec. 15.

“I watched the launch and landing of this mission, and while saying goodbye to a spacecraft is always sad, the fascinating science InSight conducted is cause for celebration,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. “The seismic data alone from this Discovery Program mission offers tremendous insights not just into Mars but other rocky bodies, including Earth.”

Short for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport, InSight set out to study the deep interior of Mars. The lander data has yielded details about Mars’ interior layers, the surprisingly strong remnants beneath the surface of its extinct magnetic dynamo, weather on this part of Mars, and lots of quake activity.

Its highly sensitive seismometer, along with daily monitoring performed by the French space agency Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES) and the Marsquake Service managed by ETH Zurich, detected 1,319 marsquakes, including quakes caused by meteoroid impacts, the largest of which unearthed boulder-size chunks of ice late last year.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona

Such impacts help scientists determine the age of the planet’s surface, and data from the seismometer provides scientists a way to study the planet’s crust, mantle, and core.

“With InSight, seismology was the focus of a mission beyond Earth for the first time since the Apollo missions, when astronauts brought seismometers to the Moon,” said Philippe Lognonné of Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, principal investigator of InSight’s seismometer. “We broke new ground, and our science team can be proud of all that we’ve learned along the way.”

The seismometer was the last science instrument that remained powered on as dust accumulating on the lander’s solar panels gradually reduced its energy, a process that began before NASA extended the mission earlier this year.

“InSight has more than lived up to its name. As a scientist who’s spent a career studying Mars, it’s been a thrill to see what the lander has achieved, thanks to an entire team of people across the globe who helped make this mission a success,” said Laurie Leshin, director of JPL, which manages the mission. “Yes, it’s sad to say goodbye, but InSight’s legacy will live on, informing and inspiring.”

All Mars missions face challenges, and InSight was no different. The lander featured a self-hammering spike – nicknamed “the mole” – that was intended to dig 16 feet (5 meters) down, trailing a sensor-laden tether that would measure heat within the planet, enabling scientists to calculate how much energy was left over from Mars’ formation.

Designed for the loose, sandy soil seen on other missions, the mole could not gain traction in the unexpectedly clumpy soil around InSight. The instrument, which was provided by the German Aerospace Center (DLR), eventually buried its 16-inch (40-centimeter) probe just slightly below the surface, collecting valuable data on the physical and thermal properties of the Martian soil along the way. This is useful for any future human or robotic missions that attempt to dig underground.

The mission buried the mole to the extent possible thanks to engineers at JPL and DLR using the lander’s robotic arm in inventive ways. Primarily intended to set science instruments on the Martian surface, the arm and its small scoop also helped remove dust from InSight’s solar panels as power began to diminish. Counterintuitively, the mission determined they could sprinkle dirt from the scoop onto the panels during windy days, allowing the falling granules to gently sweep dust off the panels.

“We’ve thought of InSight as our friend and colleague on Mars for the past four years, so it’s hard to say goodbye,” said Bruce Banerdt of JPL, the mission’s principal investigator. “But it has earned its richly deserved retirement.”

JPL manages InSight for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. InSight is part of NASA’s Discovery Program, managed by the agency’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built the InSight spacecraft, including its cruise stage and lander, and supports spacecraft operations for the mission.

Several European partners, including France’s CNES and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), are supporting the InSight mission. CNES provided the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) instrument to NASA, with the principal investigator at IPGP (Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris). Significant contributions for SEIS came from IPGP; the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany; the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich) in Switzerland; Imperial College London and Oxford University in the United Kingdom; and JPL. DLR provided the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3) instrument, with significant contributions from the Space Research Center (CBK) of the Polish Academy of Sciences and Astronika in Poland. Spain’s Centro de Astrobiología (CAB) supplied the temperature and wind sensors.

For more information about the mission, please go to: https://www.nasa.gov/insight

Karen Fox / Alana Johnson

Headquarters, Washington

301-286-6284 / 202-358-1501

karen.c.fox@nasa.gov / alana.r.johnson@nasa.gov

Andrew Good

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-393-2433

andrew.c.good@jpl.nasa.gov

Last Updated: Dec 21, 2022

Editor: Gerelle Dodson

Cover Image: The final selfie taken by NASA’s InSight Mars lander on April 24, 2022 – the 1,211th Martian day, or sol, of the mission. The lander is covered with far more dust than it was in its first selfie, taken in December 2018, not long after landing – or in its second selfie, composed of images taken in March and April 2019. Because InSight’s dusty solar panels are producing less power, the team will soon put the lander’s robotic arm in its resting position (called the “retirement pose”) for the last time in May of 2022. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Commentary by Bob Trembley

Why no brush?

In several social media posts where NASA was discussing the demise of InSight, they were asked why a simple brush (like a toothbrush) was not attached to the end of the robot arm? NASA tried their best to explain the difficulties of systems integration, materials science, costs and such…

It would be interesting to see if a brush was ever discussed as part of the original design review; I’ll bet that future missions with solar panels and a robot arm will include a brush…

It’s unfortunate that the mission is now over, but KerbalSpaceNut brings up a good point – the mission exceeded its parameters, and budgets are finite.

Maybe someday we’ll have a network of continuously functioning seismometers operating across the surface of Mars (and the Moon).

I sent my name to Mars on InSight

As with several recent missions, NASA allowed you to “send your name on the InSight spacecraft.” It looks like this trend will continue with future missions – and why not? It’s great publicity, and doesn’t cost vast amounts to implement. I’ve been saying for years that NASA has really been doing a great job when it comes to the media and publicizing missions.

Education!

NASA created the Interactive InSight Experience website, where you can deploy the various instruments on the lander, and get an explanation of what each instrument does. Great for the classroom!

And now for something completely different

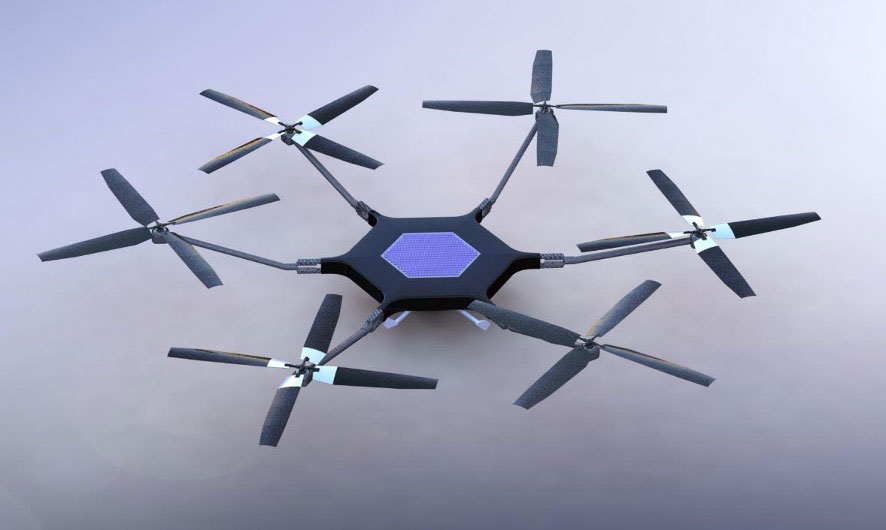

While looking at articles for supplementary materials for this post, I ran across this article about a concept for the next Mars helicopter – I gave this image a long ooOOOoooOOOH! The rotorcraft is supposed to carry between 2 to 5 kilograms of payload, but the article does not discuss scale, or give anything as a size reference. However, the first Mars Helicopter has a wingspan of 121 cm – I would guess the new one would be larger than that.