And then I wrote… In 2017 I was invited to contribute a chapter to a book called Theism and Atheism: Opposing Arguments in Philosophy (which came out finally in 2019) by my friend, the late Fr. Joe Koterski SJ, one of the editors of the book and a philosophy professor at Fordham. The chapter is long, so I have broken it into multiple parts. This is part 3; click here for part 1 and here for part 2. If you want to see the whole thing, why not check out the book itself?

The Religious Origin of Science

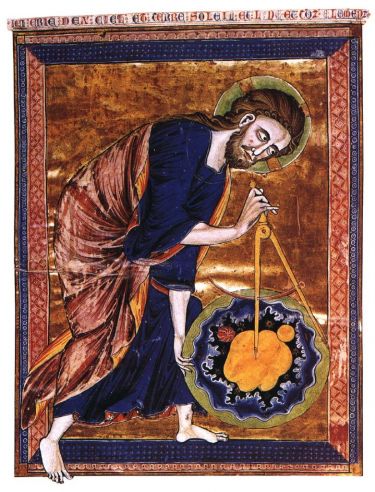

Where did science get started? The medieval universities for the first time had the magic combination. They were places where scholars could gather, where the conversation could take place. They were backed by a culture that was big enough and rich enough to support a small number of smart monks—Albert the Great being one of the first and Roger Bacon perhaps the most notable—to collect leaves and rocks, perform experiments, ask questions, look for patterns, and describe those patterns in terms of rules. As monks, they had the education and free time to pursue these studies. As Christians, they had a belief system that had cleared away the easy answers of both the pagans and the ancient philosophers.

Pierre Duhem, in Le système du monde: Histoire des doctrines cosmologiques de Platon à Copernic (1913) identified a key moment in science in 1277, when Bishop Tempier of Paris, home of the then-new University of Paris, challenged Aristotelean dominance of science by pointing out that it could not be the final word, because it appeared to have no room for God’s creative power. For example, to insist, as Aristotle did, that there could not be other worlds was to deny God’s power to make whatever he wanted.

Thomas Aquinas eventually reconciled Aristotle’s philosophy with Christian theology, but (as described in Crombie 1969, From Augustine to Galileo) the impetus to look beyond his physics inspired John Buridan (in 1355) to write about the motions of bodies in terms of what he called impetus; it was the forerunner of Newton’s concept of momentum. Nicholas Oresme (in 1377) speculated about the relative motions of earth and sky, in anticipation of Copernicus. Nicholas of Cusa (in 1440) even proposed that every star is composed of the four elements (fire, air, water, earth) making up a world with inhabitants like our own.

Modern science was ready to be born right then, until the plague killed a third of Europe. The population of Europe would not recover until around 1600, when at last William Gilbert and Tycho Brahe and Galileo and Johannes Kepler could give birth to what we finally can recognize as science, with its careful observations of nature described with mathematical laws.

Remember, this all happened in the context of the universities. (Even Galileo did most of his actual science while employed at universities in Pisa and Padua.) The universities were the places funded by the church to train leaders of the church in philosophy and theology.

Large institutions can do things that individuals cannot. It comes at a cost, of course; everyone hates bureaucracy. Still, bureaucracy makes sure that a certain minimal amount of work will get done, regardless of who is in charge or who has called in sick. That is why we put up with big science. That is why we have universities.

There are rare examples like Srinivasa Ramanujan, the remarkable self-taught mathematician from India who was able to reinvent calculus on his own, but most of us would rather take advantage of a textbook and a teacher. It saves a lot of time, if nothing else, but it means placing our faith in that professor, that institution.

It also means, at the very least, that somebody has to feed and house all those nonproductive members of society. We cannot expect a society to support a culture of science unless it is big enough and rich enough to be able to afford it. None of that would happen unless the culture decided that it was worth doing.

When the Village Disapproves

The presence of a culture that supports science provides the resources for the large project that science is and also supports each individual who must choose to go into a life of science. I once gave a talk at the College of Charleston, a beautiful campus in Charleston, South Carolina, and after the talk an undergraduate came up full of enthusiasm.

“I want to be a geologist!” he told me.

“Sounds great,” I told him.

“Yeah,” he said. Then his face fell. “But what do I tell my mom?”

He was from South Carolina, in the Bible Belt. In the culture in which he grew up, our geological ideas of billion-year-old rock formations directly contradict what he had been taught from the Bible. To be a geologist, for him, would be like declaring war against his religion, his home, his family. His mom would be ashamed of him.

Scientists are people. We have families; we have desires. Like every human being, each of us is a mixture of reason and heart, with hearts that have—in the famous words of Blaise Pascal— “reasons that reason does not know”. Like that student, we have to answer not only those desires inside us but also the desires inside the people whom we love. If our students come from families who are not proud of them for studying science, they will not study science.

After all, consider this: there are a lot of mountains and snow in India, and more people live in India than in Switzerland or Norway or Colorado (or, indeed, in all of the United States or Europe). Yet India has never won any medal in the Winter Olympics. Winter sports at that level just are not supported by Indian society. There are not enough mothers dreaming that their daughters will become figure skaters or fathers willing to pay for the equipment or the trips to the mountains to have their sons train in downhill skiing, and there are not enough competitors or competitions or trainers to hone the skills of those who might want to do that.

Science, like faith, is done as a part of a community. If we do not have the support of a community, it is not going to happen. It cannot happen. Without a community, it cannot possibly be passed on to the next generation. If the society we live in does not think that doing science is the sort of thing that will make a mother proud, we will not find very many young people who choose to study science. We will not find anyone who can teach science. Likewise, we will not find anyone who will want to learn what scientists have to teach.

Slanders about Galileo aside, the Catholic Church throughout its history has provided just such support. Likewise, the support of science in classical Muslim cultures is one reason that ancient knowledge survived to our present time. The scholarship of Judaism has also been supportive of studying the natural world, as evidenced by the notable number of Jewish scientists throughout the history of science.

If one believes that Creation is the act of one’s God, then studying it is almost a necessity. In the absence of such a belief, there is no particular imperative in atheism to study science.

Axioms and Belief in God

It is clear from the way I have formulated these axioms that I see in my Christianity precisely the source of what is needed to support and feed science (while noting that Judaism and Islam should be comparably supportive of science). Christianity insists that its followers assume that the universe is real and worth studying. Genesis describes the creation of a universe as real as the God who made it, and in the Incarnation one finds that this religion recognizes not only that reality exists but also that it is blessed.

Christianity explicitly rejects nature gods and demands that the only God to be believed in is supernatural not natural and, furthermore, one who is not the captive of whims but changeless from age to age. In the absence of nature gods, we are left with both room and necessity to find natural rules as an explanation for how nature works. Moreover, Christianity provides the physical and intellectual space to allow science to happen. It feeds scholars, and it also honors them.

The great saints in the Christian tradition are not generals or wealthy donors; even when kings and nobles get the honor of sainthood, it is because they went beyond their wealth and privilege. The things that saints do to earn sainthood are typically helping the poor and suffering, feeding the body, or learning and teaching—feeding the soul. Christianity is a religion that reminds us that we do not live by bread alone. We honor doctors who help the physically sick; we give equal honor to the “doctors of the church” who respond to our intellectual and spiritual hungers.

There is a deeper reason why I find in reason a place for my belief in God. Recall that we must accept axioms on faith before we can reason. Change the axioms, and it is possible to prove or disprove anything. That is why no “proof” of the existence of God can ever be valid, nor can we use reason to disprove the existence of God.

We do not arrive at God by the end of some chain of reasoning. Rather, God—or God’s absence—is the key axiom that determines how our reasoning develops. It is no surprise that devout people can claim to see evidence of God everywhere they look; they see it because they assume it is there in the first place. It is wonderfully pious, but it is not a proof, just a recovering of a key assumption. The same must be said for those who fail to see God.

It is possible to assume the existence of many different ideas about God and then see if the system that results from that assumption is consistent with the evidence of our senses (which is similar to but hardly the same thing as science). As we have already seen, not every choice of theology allows for the axioms that science needs.

Certainly, many choices do allow and even promote those axioms. Catholicism is one in particular that does so. By the same token, we can also declare axiomatically that we do not believe in God and construct a logically self-consistent system that explains the universe in terms of, say, accident or rigid necessity. (It is tougher to explain where those laws of chance or rigid necessity came from, of course.)

How do we choose between assuming the existence of God and assuming God’s nonexistence? The same way we make any decision based on inadequate a priori data. Study the universe. Listen to the authorities who have proved trustworthy in the past. At the end of the day, ask which explanation, the one with God or the one without, satisfies both the data of science and the instinct of the human heart.

A Return to the Questions

With this discussion in mind, perhaps we can return to the original questions and provide more than a snarky one-word answer.

Does science favor theism or atheism? I hope that now readers can see why I say that neither is favored. The choice to be a theist or atheist is an axiom choice, and it does not affect the results of the science being done. It does, however, affect the choices an individual makes about what science is done and how.

Does scientific progress favor theism or atheism? The key difference of this question compared with the previous one is the word progress. What counts as progress certainly depends on the goals in mind, and those goals can be tied to the axioms of theism/atheism. Each system has its own goals, its own idea of success, and it makes those judgments accordingly.

Do recent advances in cognitive science favor theism or atheism? Even without being cognitive scientists, we can see the fallacy of using its results, like any scientific results, as a way to prove or disprove God. God cannot be proved or disproved. Therefore, anything proved or disproved by any science is something different from God. What is more, no science proves or disproves anything; it simply comes up with richer or more complete descriptions. All of those descriptions are open to further interpretation in the light of future results and in the light of one’s axioms.

What should we make of claims by scientists to have made discoveries about religious experience and religious belief formation? Do they simply reveal some of God’s ways of communicating with us? Do recent neurophysiological studies—for example, of mystical experiences—favor theism or atheism?

Let us say that we do a magnetic resonance imaging scan on the brain of someone undergoing a religious experience. (Never mind, for the moment, the difficulty of defining such an experience or calling it up to order for the benefit of our machinery.) If such an experience can be seen to excite a certain part of the brain, the theist could claim, “See! I told you it was real!” The atheist could claim, “Aha! What you call a religious experience is nothing more than chemistry in the brain!”

If no such signal was found, the atheist could use that as proof that the experience was not real, while the theist would use it as proof of the supernatural nature of the experience.

In other words, regardless of the results, each side would simply recover the assumptions that they brought to the experiment. Such an experiment proves nothing either way.

Do studies of the efficacy of petitionary prayer and near-death experiences (or other paranormal phenomena) favor theism or atheism? Not in my understanding of prayer.

One of the most subtle points of spiritual direction is the ability to discern true impulses from God compared with impulses that have a less lofty cause. One “tell” for me of divine impulses is that they always come with a certain plausible deniability. God does not want us to have certainty; he wants us to have faith. Only then will we invest enough of ourselves in the subsequent decision to make the partnership between us work.

Do considerations from astrophysics and physical cosmology favor one view over the other? This question deserves a little more explication, especially because this is closer to my own field of study.

A few years ago Stephen Hawking claimed that he could answer the Leibniz question — “Why is there something instead of nothing?” — by invoking a quantum fluctuation of the primordial space-time continuum, a bit of gravity so to speak, as the starting point of the big bang.

Consider Hawking’s idea logically. He says that the big bang might be the result of a quantum fluctuation of gravity. He then identifies the origin of the universe at the big bang with the act of God’s Creation. He concludes that because he can explain that big bang with gravity, there is no such act and thus there is no such God.

By his own reasoning, that is not true. If God is defined as the instigator of the big bang and the instigator of the big bang is shown to be gravity, then we must conclude logically that gravity is God. (At this point I am tempted to interject that perhaps he thinks that is why Catholics celebrate Mass.)

He misunderstands two concepts here. He thinks that Creation is something that occurs only at the starting point, and he thinks that God is the thing that kicks off everything at the starting point (and nothing else). A god who was responsible for the big bang, within a universe of preexisting space-time and scientific laws, would be no more than a nature god like Zeus or Typhon, throwing lightning bolts or causing volcanoes to erupt — one more force alongside gravity and electromagnetism.

Hawking is right not to believe in such a god. No Christian should believe in such a god either. We rejected the nature gods of the ancient Romans and Greeks (and suffered persecutions as a result), and we must reject this idea of God as well.

The God of Genesis is one who is already present before space and time have been created, before there are “laws of physics” to be used to explain how things work. Because God is outside of time, the act of will that makes this universe exist is also an act that is not confined to any one place or time. Creation is occurring all the time, at every moment. Every second that exists so that we can be aware of its existence is a miracle; there is no reason within nature itself to explain why nature exists.

This is a classic point of philosophy and of reason, and it relates to the idea that every act of reason must start with axioms that are outside the realm of reason to prove or disprove. The meaning of this universe cannot be found within the universe, any more than the reason why there are chairs can be explained without noting the existence of something that is not a chair, using that chair to sit down.

Incidentally, the Belgian scientist who first proposed the big bang theory, Georges Lemaître, understood this point very well. He refused to identify the origin point of the big bang with the act of God’s Creation. Of course, unlike Hawking, Lemaître had also studied theology and philosophy; along with being a scientist with doctorates in math and astrophysics, Lemaître was a Catholic priest.

Do considerations from quantum mechanics favor one view over the other? This is the latest temptation in the naturalist view of religion. Some religious people fear that Newton’s laws lead to a deterministic universe where no freedom of will could exist, and they find in quantum uncertainties a place to hide free choice of the will after all. This is just another version of the God of the Gaps, holding God hostage to future developments in quantum theory, if nothing else.

The theologically more honest answer, both then and now, is to recognize that freedom of will does exist, whether or not Newton (or quantum theory) has room for it. Nor should one be surprised that there are aspects to reality that go beyond scientific explanation. Science is human; it is limited. By design it chooses carefully the phenomena it is capable of describing. It must remain agnostic about experiences outside of its expertise.