And then I wrote… In 2015, for the 80th anniversary of our move out to Castel Gandolfo, the Vatican Observatory held a week-long seminar for our scientists, adjuncts, and friends. The proceedings were published by Springer in a book edited by Gabriele Gionti and Jean-Baptiste Kikwaya Eluo. Last week, in part 1, we talked about why we need to do outreach and a few strategies for negotiating interviews with the press. This week, we’ll look at how to talk to them once the interviews begin…

What’s the story?

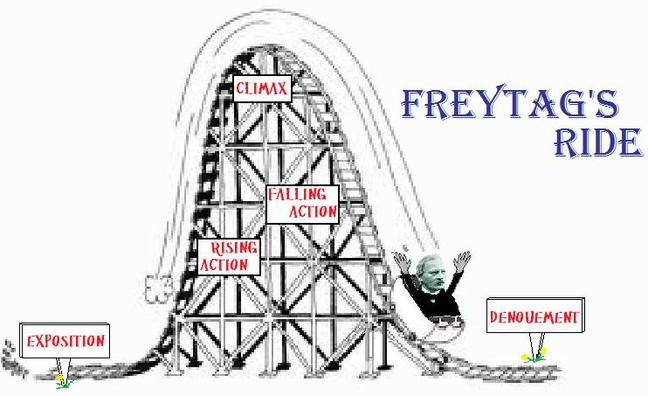

It’s not by accident that articles in a newspaper or a television broadcast are referred to as “stories”. And so when preparing what you want to say to an interviewer, it’s important to think of your message in terms of the classical structure of a “story.” In 1863 the German playwright Gustav Freytag, following ideas on literary analysis going back to Aristotle, outlined five stages in any typical story: exposition, development, climax, consequences, and dénouement.

A story starts with an exposition, a setting: Where are we? who are the protagonists? A place and people we care about… the poor orphan with the funny scar living under the stairs at Number 4, Privet Drive; the peaceful countryside with lovable hobbits.

A story lures you in with a problem, a conflict, a mystery; it makes you want to know what happens next, what happens when the wizard visits the orphan or the hobbits, and drags them all away from home.

A story has a central point, a climax, when the main character makes a crucial decision, when someone uncovers the key piece of information and everything you thought you knew is changed.

And the decision, the information, the main moment has consequences. It matters. We know how it matters, within the realm of the story, because we’ve been given the set up in the first place, back when the story began. So we know about the evil wizard who killed the hero’s parents, we know about the evil ring that can control all the other rings of magic but corrupts one’s soul in the process. But it also matters outside of the universe of the story; inside our own personal universe, it matters in a different way; it matters enough that we want to keep turning the pages to find out what happens next. We have to see how the decision plays out.

And then we come to the end, the resolution, the denouement. For a story to satisfy, you need to have a moment at the end to step back, catch your breath, and just take in the scenery… look over the landscape now, where Middle Earth will never be the same; where a new generation boards the train to Hogwarts.

So how do you apply this to preparing for an interview? Your “story” need the same parts. You describe the problem that you’ve been working on. You describe why it’s a problem – and why you needed that clever or difficult or special thing you did, to make it all work. You describe your brilliant contribution. You describe what came of it. And then you sit back, see how it changes all our ideas about the origin and evolution of the universe, and why you’ll be asking for another grant next year to keep up the good work.

Who are these guys?

This exercise automatically brings you to addressing questions you might otherwise overlook. For example, when describing the “setting” of your story, you need to know what it is you are assuming your audience already knows. And in order to do that, you have to know who your audience is. What level of education is the journalist aiming at? Are they writing for Science or the Weekly World News?

To know that, you have to do some research on the journalist themselves. What is their outlet? What other stories have they written? What sort of details do they like to include in their stories? In other words… before you even agree to the interview, do an internet search on the person requesting the interview.

If the journalists are coming with a film crew, find out the title and brief description of their program, the names of all of those who will be on the filming crew, and date and time of the shoot; and find out what their agenda might be! In this context, be aware that the major specialty cable networks like The History Channel or The Discovery Channel may have started out as attempts at quality television, but they are quality no more. The lure of large audiences from so-called “reality shows” has driven the better documentaries off those channels, with the result that if you are filmed for a show destined for cable TV you are likely to be seen alongside the worst sort of UFO or astrology rubbish.

As a result, one of the simple rules of thumb that I have adapted for the Vatican Observatory is that we do not accept film crews for any of the cable networks anymore; not Discovery, not History, not even National Geographic. It is too damaging to our reputation as a serious scientific institution to be included alongside the other programs they run.

Another rule of thumb is that if the web site of the reporter or program requesting an interview mentions aliens or UFOs in any form, no matter how seriously they claim to be, we will not allow them to interview us. Period. (This rule comes as the result of one one of those learning-mistakes; we have been burned badly in the past by writers who claimed one thing while interviewing us, and then their program and book completely misrepresented what we had said.)

Finally… trust the smell test. If it smells funny, even if you can’t put your finger on the problem, don’t let it in your door.

(Of course, there are exceptions to all these rules. A journalist who has earned your trust, one with whom you have had previous good experience, can be trusted.)

Before they arrive (the reporters, not the aliens!)

Once you have agreed to do an interview, your work has only begun. First of all, all journalists must be made aware of the Vatican’s rules for reporter coming for an interview (including filming or other recording) on Vatican territory. Reporters need to obstain written permission from the Vatican before they can take record any sound, pictures or film on site.

The details of how they can obtain these permissions may change over time, but the Vatican Observatory web site www.vaticanobservatory.va [or https://www.vaticanobservatory.org/press/ ] should have links to the current rules and addresses of those who need to give permission. While the rules are not quite as strict for recording in Arizona, there are University of Arizona regulation and Forest Service permits that must be cleared before filming can be done on campus or at the telescope on Mt. Graham.

Next, before the journalist arrives, prepare a very clear statement of what you want to say. Write it out, write it down, rehearse how you will say it! Anticipate the most likely questions; prepare an initial brief answer, a sound bite that’s exactly 7 seconds long. Then prepare a longer answer, say 30 seconds, which you can use if you are given the time to expand on your story. Be prepared to illustrate your point with examples and analogies. Always restate the initial brief answer at the end.

During the interview

During the interview itself, there are some useful points to remember. First and foremost, passion sells your story. If you’re not excited about your result, your story, and you don’t communicate that to the reporter (and ultimately to the audience) then they will have no idea that there’s anything in what we are doing that is worth being passionate about.

There are also some simple rules that will make the journalist more likely to use your answers and less likely that you will make a terrible faux-pas in public:

Give your answers in complete sentences that make sense even without the question.

Don’t say anything you wouldn’t want to see on the front page of your country’s biggest newspaper. Nothing is ever “off the record.”

Don’t repeat the reporter’s framing of the question, especially if you want to refute it; use only your words to convey your ideas, not theirs.

Don’t be tricked into saying more than you want to say by fear of “dead air.” When you have said your piece, stop. Filling long pauses of “dead air” is their problem, not yours!

Avoid any temptation to be clever or sarcastic; it can backfire. No… rather, let us say, it will backfire. Always.

If you are being filmed, dress for the camera. Members of the Observatory should preferably be dressed in clerics for any formal interview. In any event, avoid clothing with stripes, as they can show up on video as odd Moiré patterns; and avoid material that makes noise when you move, because any such noise will be magnified by lapel microphones.

A lot of what the audience will remember about you comes not from what you say but how you look. Be aware of your body language. Keep your upper torso straight; head straight, shoulders down. Avoid looking defensive: don’t cross your arms or clasp your hands, but hold your arms and hands out to signify you have nothing to hide. Use your hands for emphasis, within reason. And don’t forget to make eye contact with interviewer!

Likewise, your face conveys a lot even when you are saying nothing. Smile when appropriate; astronomy is fun! Keep your mouth closed when listening. Be animated: open your face up, change your expression, let your eyebrows raise when appropriate. Don’t lick your lips or bite your lip. And in general, don’t touch your face with your hands.

When the interviewer is hostile… or clueless

But then… having come prepared to tell your story, what happens if the reporter never gets around to asking you about what you wanted to say? There’s a trick to use, called “The Bridge”. Listen to the reporter’s question, acknowledge it, but then create a “bridge” to the answer you really want to give. That’s when you can move to your previously prepared message.

If the questions are difficult, if the journalist is being aggressive or appears to be looking to trap you, be calm but don’t follow their lead. Let your answers be driven by your message, not their questions. Don’t repeat the “bait” word that the reporter suggests, but respond using only the words that you want to use to describe your ideas.

Whether hostile or not, there will always be questions that may throw you for a loop. Don’t be afraid to say you don’t know the answer to a question. If you can, refer the reporter to someone who does know, better than you. (And if you lose your train of thought… pause two seconds; tilt your head; act like you’ve just had a bright new idea. And then start talking about whatever you really wanted to talk about. Take advantage of the fact that we’re astronomers – don’t be afraid to look like the absent-minded professor!)

Bad news

If you have bad news to report, certain basic rules can help keep your interview from making the matters even worse. Don’t respond with hostility or emotion. If you can’t answer, give a reason why. Never say “no comment”; if you say “no comment” you actually wind up conveying the idea that the premise of the hostile question is true but you aren’t prepared to admit it in public!

Keep personal opinions to yourself. Never lie. Never guess or speculate; especially, never speculate about the motives of people who disagree with you.

And one of the hardest rules to keep, but one of the most important: never answer a “hypothetical question.” We cannot say what we will do, if… aliens are discovered, or the telescope crashes, or terrible poisons from space are emitted from a freshly fallen meteorite. To answer such questions, first of all, dignifies the often absurd propositions; and furthermore, the way we will respond in any such event will depend so much on the details of the situation that can’t possibly be known ahead of time. You do not want to go on record saying that you would do or think one thing, only to have to backtrack when the reality of a situation shows that a completely different response is more appropriate.

After the interview

The work does not stop once the interview is over. Learn from your experience: what worked? What didn’t?

Getting “always the same questions” is OK: there’s comfort in knowing what is likely to be coming, what sort of answers work, how to pace the story, what details can be skipped over, where the laugh lines are.

Most scientists who are not used to being interviewed will inevitably have a feeling of exhaustion, let-down, or concern that things may not have gone the way you like. The biggest (but hardest) thing to do after the interview is over, is to forget about. At the end of the day, don’t worry if things go wrong. Don’t make a big deal of minor errors; corrections often just spread the error further. If there is a major error, you can contact the reporter; but whatever you do, don’t contact their boss!

Remember, at the end of the day, there is no such thing as bad publicity. Anything that creates awareness of astronomy or the Specola is good. Indeed, more often than not, the reaction of most people even to bad publicity is “gee, I didn’t know the Vatican had an observatory!”

And that, in turn, reminds us why it is worth the headache of making ourselves available to the press. It can be a lot of fun! Your family and friends get to see your name in the paper! And as the result of such interviews, I’ve gotten to meet a number of interesting (and famous) people, such as the science fiction writers Terry Pratchett and Gene Wolfe; the Astronomer Royal, Sir Martin Rees; and the astronauts Nicole Stott and Roberto Vittori. More people ask me about meeting Stephen Colbert than about meeting the Pope!

And in fact, this sort of publicity has garnered real benefits to the Specola up to now. Many email fan letters, from folks who first learn about us and the Church’s support of science, arise from our interviews. They can often be heartening stories of young people who were afraid a life of science might lead them away from God, or from older scientists who just like to be reminded that they are not alone in their lives of faith.

And in fact, it was a Sky and Telescope article that led to Rich Friedrich joining the Vatican Observatory Foundation; for many years he has served as chairman of our board.

Conclusion

Popularizing our science is just as much work as writing a scientific paper. It takes a special set of skills. If you aren’t good at it, admit it: ask for help. Give help to others who ask.

And it’s important. We astronomers are here to feed a common human hunger to know about ourselves and our place in the universe. The Church supports us not merely to show the world that she supports science, but because studying creation is a sure route to getting to know the Creator. It is our job as astronomers and Jesuits to show the whole world where one can find God in all things, on Earth and in the heavens.