(And Then I Wrote…) In order to let my backlog of “Across the Universe” columns build up a bit, I am republishing a selection of other articles that I have written and published in various places…

Keeping up my pattern this month of book reviews, I include here a review of a The Observer’s Guide to Astronomy, Volume I. edited by Patrick Martinez in the late 1980s; translated by Storm Dunlop into English in 1994. My review ran in Icarus volume 117, pp. 216–217, in 1995. So why bother reading about a book that is now more than thirty years old? As I argue at the end of the review, “This book, written for the amateur today, may find its greatest long-term professional importance in the future as a lucid and detailed record of how astronomy used to be done, way back in the 20th century.”

It also shows my typical style of book reviewing. All book reviews are personal opinions; and so I am not shy about injecting personal stories into the review!

[In order to read the rest of this post, you have to be a paid-up member of Sacred Space, and logged in as such!]

The Observer’s Guide to Astronomy, Volume I. Edited by Patrick Martinez; translated by Storm Dunlop. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1994. 594 pp.,

On July 16, 1994, as the first fragment of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 approached Jupiter, L was sitting in the dome that houses the 24-in. Cassegrain telescope al Castel Gandolfo, ltaly, preparing to look for flashes of light echoing off the surface of Europa. L had traded in my status as a theorist to try my hand at professional observations of this once-in-a-lifetime event. Our equipment was a 20-year-old (but still functional) photometer borrowed from Bill Hubbard at the University of Arizona.

Meanwhile, in the telescope dome next to ours, two amateurs had borrowed our elegant but technically “obsolete” 16-in. refractor to gaze at Jupiter itself during the impacts. Claudio Costa, an electrical engineer from Rome, and Wolfgang Beisker, a technician who builds CCD devices for a biology lab in Munich, are two amateurs who normally specialize in observing and recording occultation events, part of a network of such observers throughout the world affiliated with the European section of IOTA, the International Occultation Timing Association This night they had attached one or Wolfgang’s state-of-the-art CCD cameras to our ancient telescope, and they were recording their images with a portable PC.

Our “professional” results that night were, at best, ambiguous. By about 10:30, long after fragment A should have impacted, I still was not sure that we had seen anything. But then a shout came from the other dome. The amateur had no question about what they had seen. I rushed in and watched with them as a huge black spot in the clouds of Jupiter slowly rotated into view.

I wound up spending months playing with my data, beating down the noise, comparing notes with other observers at several conferences, writing up the results… and L am still not sure what L saw. Claudio and Wolfgang have no such concerns. They were among the first people in the world to have seen the first SL/9 impact site; they knew it the moment they saw it, and they needed no conference talks or publications to confirm their thrill.

Amateur astronomy, especially at the advanced level of groups such as IOTA or ALPO (the Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers), has always shared an odd friendship with the professional community. They envy our ability to command time on the best telescopes: to live on the cutting edge or knowledge (indeed, to create that cutting edge); to actually get paid to do what they do for love. We envy them the freedom to observe what they want, when they want; their freedom from committees, funding woes, referees’ reports; their ability to still be in love with, and be excited by, the sky.

The Observer’s Guide to Astronomy was written for such serious amateurs. It was originally compiled and edited in France by Patrick Martinez in 1987; an English edition bas now been made available by Cambridge University Press, translated by Storm Dunlop. lts two volumes include 20 lengthy chapters by advanced amateurs, giving nuts-and-bolts details of how they make serious observations with their own equipment. Volume 2 covers mostly deep-sky observing; Volume 1, reviewed in detail here, concentrates on solar system observations.

Though the translation is smooth and idiomatic, by their nature the chapters are detailed and technical; it is not a book that one reads cover-to-cover to while away a cloudy evening. And yet it is the sort of book one can pick up, open to any page, and learn something new and interesting about a familiar topic.

For the reader who is a professional astronomer, not an amateur, one wonderful thing about this book is the way it lets us see old friends in a new light: from the point of view of an amateur.

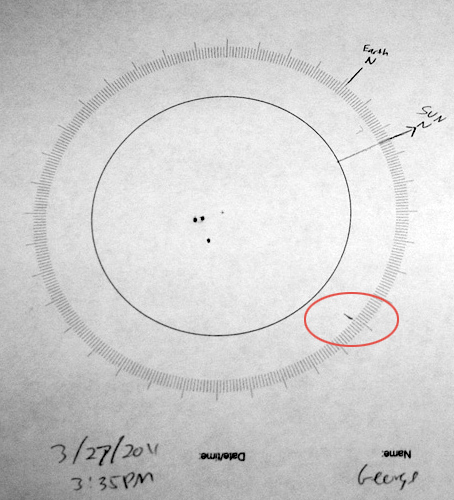

The first chapter (by M. J. Martres, R. Boyer, F. Costard, J. M. Matherbe, and G. Olivieri) gives a lucid explanation of how amateurs can record sunspots and flares, describing in some detail how to go about observing and photographing nares in H-alpha and other wavelengths using amateur equipment. The second chapter (by J. R. Leroy) follows up on this one by describing the design of a coronagraph suitable for amateur work. Like all the chapters, this one is lavishly illustrated with excellent photographs produced by amateurs with the equipment described. In Chapter 3, S. Koutchmy describes the science behind solar eclipses and the detailed observations of the corona within the reach of the amateur.

The first chapter (by M. J. Martres, R. Boyer, F. Costard, J. M. Matherbe, and G. Olivieri) gives a lucid explanation of how amateurs can record sunspots and flares, describing in some detail how to go about observing and photographing nares in H-alpha and other wavelengths using amateur equipment. The second chapter (by J. R. Leroy) follows up on this one by describing the design of a coronagraph suitable for amateur work. Like all the chapters, this one is lavishly illustrated with excellent photographs produced by amateurs with the equipment described. In Chapter 3, S. Koutchmy describes the science behind solar eclipses and the detailed observations of the corona within the reach of the amateur.

Chapter 4 (by S. Chervel and M. Legrand) discusses lunar observations. Among the aspects of lunar observing, the authors explain the Moon’s motions in more detail than I have ever seen in an amateur-oriented book, and they show how such detail can be important to the amateur. For instance, at times in its orbit the Moon can move by as fast as 0.26 arc-sec per second in declination – the direction not corrected by most amateur motor-drives; yet this is fast enough to blur a long-exposure, high magnification photograph.

Another example from this chapter, typical of the detail in the whole book, is the extensive discussion of the sorts of observations and data reduction needed to determine the heights of lunar features from their shadows, including an error analysis. A significant part of this chapter discusses transient lunar phenomenon, a subject about which most astronomers are extremely skeptical; and yet, for that very reason, it is a subject that lunar observers should be aware of. (The absence of consistent, widely seen transient phenomena on the one celestial object that is almost certainly under observation at any time by some amateur, somewhere in the world, is probably the best argument against its existence that I can think of.)

In Chapter 5, J. Dijon, J. Dragesco and R. Néel discuss amateur observations of planetary surfaces, concentrating on drawings and photographs of Jupiter and Mars. The chapter begins with a fascinating discussion of the human eye as a scientific instrument, and goes on to describe the important role that small telescopes (0.4- to 0.6-m aperture) can play. Chapter 6 (by B. Morando) is dedicated to amateur observations or planetary satellites; the primary emphasis is on mutual phenomena of the Galilean satellites.

Thirty years after this book talks about it, we actually are going to visit Psyche! Artist’s-concept of NASA’s Psyche mission. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Arizona State Univ./Space Systems Loral/Peter Rubin

Thirty years after this book talks about it, we actually are going to visit Psyche! Artist’s-concept of NASA’s Psyche mission. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Arizona State Univ./Space Systems Loral/Peter RubinMost of the material on asteroids that makes up Chapter 7 (by J. Lecacheux) will be familiar to readers of Icarus or of the University or Arizona’s books, which make up the primary source of the author’s background material, but I found it fascinating to see how the subject was treated by the amateur author. For example, in discussing the classification system of asteroids he writes: “Photometric methods only tell us about the surface layer of the body, and not about the material in its interior… it is by no means certain that the analogies with meteorites are completely justified. For example, it is by no means scientifically proven that 16 Psyche is a lump of metal 250 kilometers across. To be certain, we would have to visit it!” This, written in 1987, is an excellent summary of the debates that have raged in the asteroid community during the 1990s.

Appropriately for a book aimed at amateur observers, most of the discussion in this chapter centers on finding and tracking asteroids. It includes an excellent introduction to the technique of (and need for) astrometric measurements, an area where the amateur’s time and energy can make significant contributions beyond what most professional observatories can hope to supply. As the author points out, bright skies do not affect measurements of positions; and many local observatories may have old but perfectly functional measuring machines gathering dust because no one can afford to hire the staff to use them. This is certainly true of the Vatican Observatory in Rome.

J. Merlin discusses the observation of comets in Chapter 8. Comet discoveries and observations have long been a field where amateurs have thrived (the Shoemaker-Levy team being the most famous example of professional/amateur cooperation) and appropriately enough, at 170 pages, this is by far the longest chapter in the book. It concentrates on the observation, drawing, and photographing of known comets as well as providing a lengthy, detailed description of the sorts of observations needed to establish the discovery of a new comet. Chapter 9 (by R. Boninsegna and J. Schwaenen) discusses a topic close to the hearts of my SL/9-observing friends Claudio Costa and Wolfgang Beisker: observing and timing occultations. Again, amateur work in this field has been invaluable and the chapter provides detailed instructions on how to do the kind of observations needed.

The last chapter in this volume (by R. Futaully and A. Grycan) treats a subject that in many ways illustrates the difference between amateur and professional observation. How many papers are presented at a DPS meeting about ground-based observations of artificial Earth satellites? And yet this is an active area of amateur research, and one which can have significant implications both for the future of space travel – keeping track of space junk is not a trivial business – and for ground-based observations of transient phenomena. Glints off satellites can easily be mistaken for stellar flares, optical counterparts to gamma-ray bursters, or transient lunar phenomenon. But the real motivation for amateur work in this part of the field is much simpler: satellite glints are fun to watch for.

In summary, then, this is a marvelous book, one that any serious amateur would be delighted to have on the bookshelf. As a text for amateurs, however, the book also has its drawbacks. It is clearly geared to the most serious observer; the presence of many equations and detailed tables and the absence of flashy color pictures will (rightly so) discourage the casual stargazer. Furthermore, there is in this book the ambiguity that haunts all amateur astronomy: does one observe to do serious science, or for the sheer glory of knowing the sky in intimate detail? Depending on your answer, your approach to astronomy will be very different; yet most amateurs, including the ones who wrote this book, are unwilling to forgo one motivation for the other.

However, the most serious deficiency of this text is that much of the material is nearly 10 years old. Indeed, this book was written at an interesting time in amateur astronomy: the 1980s saw the end of an old era and the beginning of a new one. At that time most amateur observers still recorded their data by hand, depending on their own “personal equation” to estimate everything from sky conditions to magnitude differences, and data reduction, if done at all, was done by hand.

To this end, many pages in this book are dedicated to reproducing what is essentially fancy “graph paper,” for example, the various grids used to plot sunspots, that take into account the nonsphericity of the Sun and the various ways it can be oriented toward the observer. However, a simple computer program today can produce the same sort of chart; more to the point, a sophisticated computer spreadsheet could immediately translate the x-y positions of a sunspot into accurate solar latitude and longitude without resorting to any such chart in the first place.

Today CCD equipment is cheap and commonly used by amateurs, a topic only hinted at in this volume. (A separate chapter in Volume 2 treats CCDs.) The Clementine results from the Moon have made much of the discussion of “Luna Incognita” in Chapter 4 moot. And new telescope designs, most significantly the explosion of large Dobsonian reflectors on the amateur scene but also the greatly improved figures of mass-produced lenses and mirrors (via computer control of the grinding and testing process), have thrown into question much of the common wisdom about what kind of telescope is best for a given type of observation.

On the other hand, these very deficiencies may be the greatest reason this book is indispensable in a professional planetary astronomy library. The historical record of amateur (and professional) observations from the 19th and 20th centuries is still of great importance today, and will continue to be in the future. But as new technology takes over the field, we are beginning to lose the institutional memory of how such observations were made. This book, written for the amateur today, may find its greatest long-term professional importance in the future as a lucid and detailed record of how astronomy used to be done, way back in the 20th century.