And then I wrote… In June of 2016 I was invited to give two lectures at Loyola University of Maryland for their annual Cosmos and Creation seminar. What follows is based on those talks…

Let me pivot and make an equally startling statement for those of us who are people of faith. Just as the scientist is, in some ways, not so far from the fundamentalists, we believer must also remember that are also almost atheists. By believing in the one God of Christianity, there are many, many other versions of God that I do not believe in. Indeed, I only believe in one more God than Stephen Hawking does.

Though I have met many friends over the years who call themselves atheists or agnostics, it was at one particular moment when it suddenly hit me how much I had in common with the atheists.

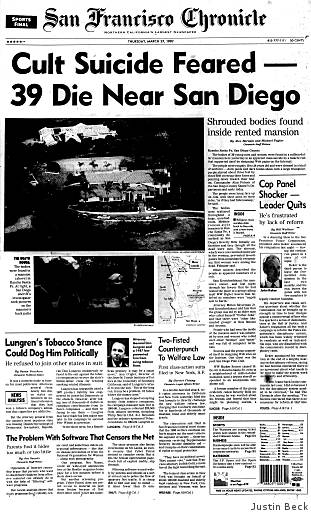

Remember Comet Hale-Bopp and the crazy Heaven’s Gate cult that promoted mass suicides triggered by the comet as a route through the End Times? In response to them, an astronomer friend decided to deal with this craziness as only an intellectual could: he organized a conference about comets and religion, through an organization he belonged to called the Democratic Secular Humanists of America.

The conference had a series of hour long talks about comets and philosophy – I gave one of them – with a few hundred good folks in the audience. I had lunch with a number of the attendees. They were young, maybe mid 30s, intellectually curious, very friendly. Not surprising given their ages, the lunch conversation soon turned to families and schools and the problems of raising kids. What I remember most was one of the moms complaining, “It’s really hard to raise good atheist children nowadays because our society is so saturated with religion. It is everywhere!”

I don’t remember what I had for lunch; I was too busy biting my tongue. How often had I heard almost the exact same words, with one slight twist, from my evangelical friends?

That afternoon my friend, who teaches astronomy at the local community college, scheduled himself to give his standard hour long “Big Bang” lecture. He started by asserting that there are only three distinct and, of course, mutually exclusive ways of understanding the universe: there’s religion, but we all know, religion is absurd. (The audience nodded in agreement.) Then there’s philosophy; but philosophy is only a bunch of nonsense words. (They nodded some more.) Then, finally, there’s Science! Smiles and grins all around.

But as he started outlining what Science could tell us about the origin of the universe, the smiles started to fade, and by the time of the question and answer period much of the audience was outraged. The Big Bang? Relativity? None of that made any sense to them, it sounded as much like gibberish as philosophy did. And when my friend tried to point out that the best scientists and mathematicians of the day were behind the Big Bang, they were outraged even more. He was arguing entirely on an appeal to authority!

The split between speaker and audience illustrates an interesting divide in the skeptic mindset. There are skeptics who reject all religion precisely because they reject all authority. And there are other skeptics who reject all religion because in their minds it’s a rival to the authority that they accept instead: the authority of science.

Even science depends on authority. We can’t possibly derive every equation, produce every data point, define every term anew by ourselves. (I wouldn’t trust my own work enough to even try.) We trust the giants whose shoulders we, like Newton, must stand upon.

Those of us in science are familiar with authority, and we respect authority, precisely because we are authorities ourselves. It’s an attitude familiar to us from the story of the Centurion’s Servant, as told in Matthew’s gospel:

A centurion came up to Jesus, asking for help. “Lord,” he said, “my servant lies at home paralyzed, suffering terribly.”

Jesus said to him, “Shall I come and heal him?”

The centurion replied, “Lord, I do not deserve to have you come under my roof. But just say the word. For I myself am a man under authority, with soldiers under me. I tell this one, ‘Go,’ and he goes; and that one, ‘Come,’ and he comes. I say to my servant, ‘Do this,’ and he does it.”

When Jesus heard this, he was amazed and said to those following him, “Truly I tell you, I have not found anyone in Israel with such great faith. I say to you that many will come from the east and the west, and will take their places at the feast with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven. But the subjects of the kingdom will be thrown outside, into the darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.”

Then Jesus said to the centurion, “Go! Let it be done just as you believed it would.” And his servant was healed at that very hour.

It’s a lovely illustration of how someone who is used to authority can understand and appreciate authority in others. Jesus “teaches with authority” we are told in many places in the Gospels. That understanding of authority is a common ground between Jesus and the Centurion.

He speaks to the Centurion in a very different way than he speaks to the Scribes and Pharisees. He doesn’t cite scripture or argue points of theology. He also does not reject the Centurion just because he is a Roman. He takes the Centurion for who he is, meets him where he lives; indeed, even literally offers to go to where the Centurion lives.

Notice also, once again, how Jesus is very aware of both the person He is talking to, and to the audience who’s overhearing them both. He uses the opportunity to teach the crowd, making it clear that the outsiders like the Centurion are closer to the Kingdom than the self-righteous in the audience. That’s something for us to think about; it may well be that our closest allies in the long run are the skeptics and the atheists.

(Also notice one last, but important thing. In all the teaching that Jesus does at the moment, he does not ignore the concern at hand – he does get around to curing the Centurion’s servant.)

With this in mind, I want to go back to the thesis of my friend’s talk to his fellow “secular humanists.” He asserted that our understanding of the universe can be divided into religion or philosophy or science as distinct “non-overlapping magisteria.” That phrase was coined by the sympathetic skeptic Stephen Jay Gould in his book, Rocks of Ages, which tried (and failed) to reconcile his understanding of science with his understanding of faith. I think that desire for separate, non-touching realms of science and belief is at the root of a lot of misunderstanding between skeptics and believers.

There’s a temptation to divide our experience into separate categories, faith versus science, emotions versus logic. But it’s a false division. Real humans are not just a mass of feelings or else just cold reasoning machines, like the Star Trek characters Kirk and Spock. (Heck, even Kirk and Spock were not really just Kirk or Spock.) Our understanding of logic was developed by the scholastic theologians of the middle ages; and as Gödel’s theorem show, all logical systems must begin with assumed axioms. What’s more, scientists rely on hunches – we call it, experience – to decide which possible theories to explore or which experiments to do. Galileo was a convinced Copernican fifteen years before he ever even heard of the telescope.

So why do skeptics (or indeed fundamentalists) think that hunches and reason are mutually exclusive, non-overlapping ways of viewing the universe? Oddly enough, it was conversation I had with Captain Kirk that gave me an insight.

How I wound up talking to William Shatner, the actor who played Captain Kirk … it’s a long story. But when I described myself as a Jesuit scientist, he was flabbergasted. “Wait a minute, wait a minute!” he said. And as we talked further, it something so obvious to him suddenly became clear to me that I had never grasped before. He saw religion and science not just as two separate domains, but as two competing sets of truths. Two big books of facts.

And what should happen if the facts in one book contradict the facts in the other?

Of course. If you think science or religions as big books of facts, then you could imagine that kind of conflict.

But I know that science is not a big book of facts. The orbits of the planets are facts; you can describe their paths by Ptolemy’s epicycles or by Kepler’s ellipses and both descriptions can be tweaked to give equally accurate descriptions of those orbits: the facts. But only Kepler’s ellipses will lead to the insight of Newton’s law of gravity.

Science is not the facts of the orbits; it is what you do with those facts, the conversation you have about those facts, the insights that come from the facts. And doing science also means being open to the realization that Newton’s laws, too, are not the last word. Not even Einstein’s General Relativity, the modern replacement for Newton, is the last word. I suspect the science of 3016 will look very different from what we’re teaching today.

In the same way, our faith is not based on rigid certainties that all fit in a book either. I had surprised William Shatner the phrase that Anne Lamont famously used to describe faith: “the opposite of faith is not doubt; the opposite of faith is certainty.” That was completely the opposite of what he thought faith was about.

He’d heard the phrase “blind faith” and thought that meant accepting something as certain without looking, or worse, closing your eyes to the facts and proceeding on emotion. But that’s not faith at all. To the contrary, remember what Moses says to his people after giving the the Tablets of the Law: “do not forget the things your eyes have seen or let them fade from your heart as long as you live. Teach them to your children and to their children after them.” It’s not, “close your eyes” but rather, “teach what you have seen.”

Blind faith is not walking with blindfolds, blinding ourselves to truth. It’s proceeding after we’ve done everything we can to see, and still can’t see everything. All of life is making crucial decisions on the basis of inadequate information.