[Trappist One is not the only time that beer and astronomy have mixed; I used the beer bottle above as a scale for the olivine samples suggested to be analogs for interplanetary dust…]

And then I wrote… in 2016, a team of astronomers led by Michaël Gillon of the STAR Institute at the University of Liège in Belgium announced the discovery of three planets around a star observed by one of their telescopes, TRAPPIST South. When they published an update of their results in the scientific journal Nature that expanded the number of planets in this system to seven, the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano invited me to reflect on the significance of this discovery.

They published it, in Italian, on February 23, 2017, under the title: Sulla scoperta di sette pianeti simili alla Terra: La birra e il telescopio. (On the discovery of seven Earthlike planets: the beer and the telescope). This is the English text that I sent them, published here for the first time.

Looking out for neighbors

“Do you believe in life elsewhere in the Universe?” It’s a question that astronomers are asked all the time. It is the right question: life in the universe is, so far, a question of belief. We have no data that says such life exists. But our faith that life is there is strong enough that we’re willing to make the effort to search for it.

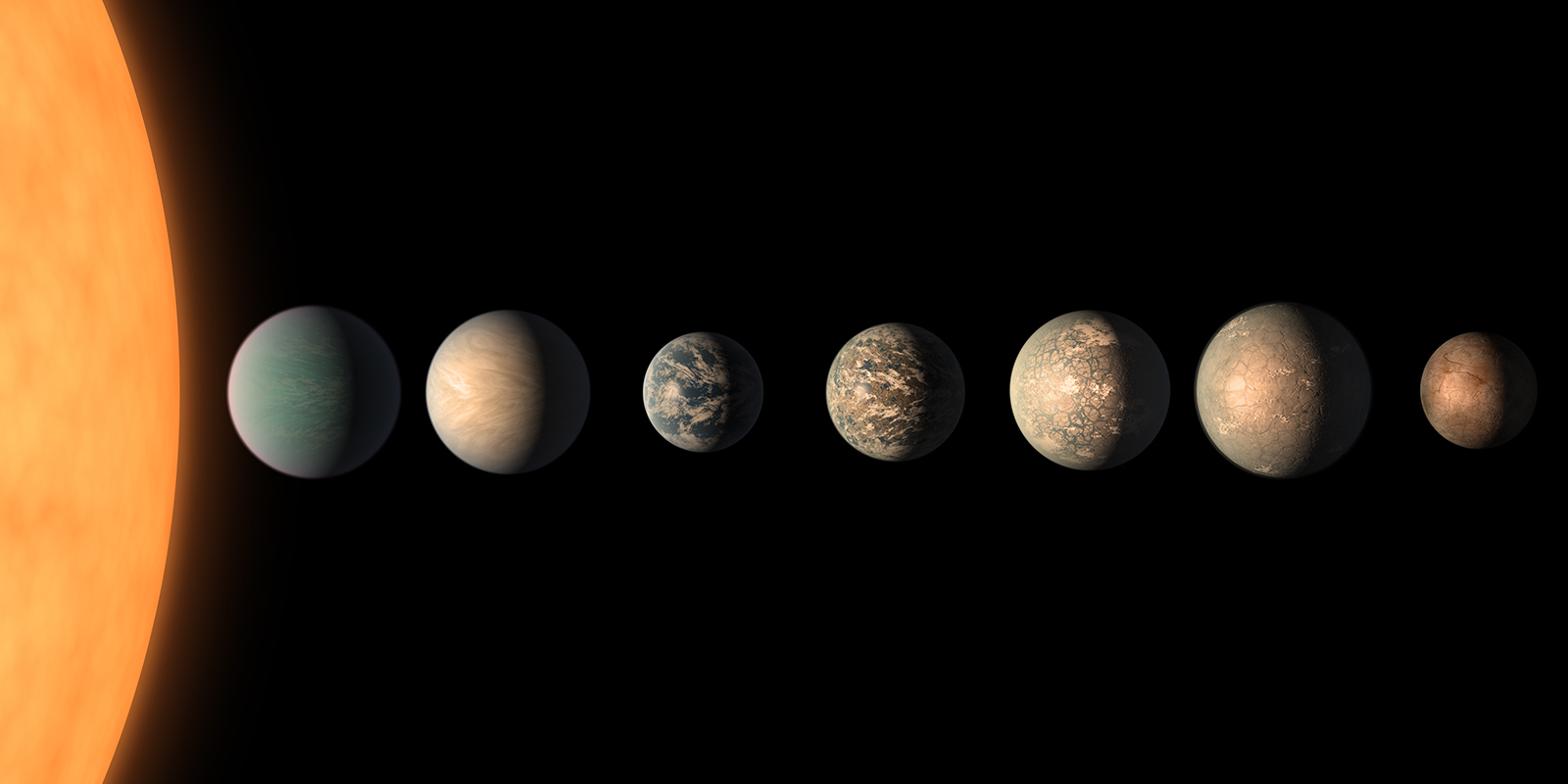

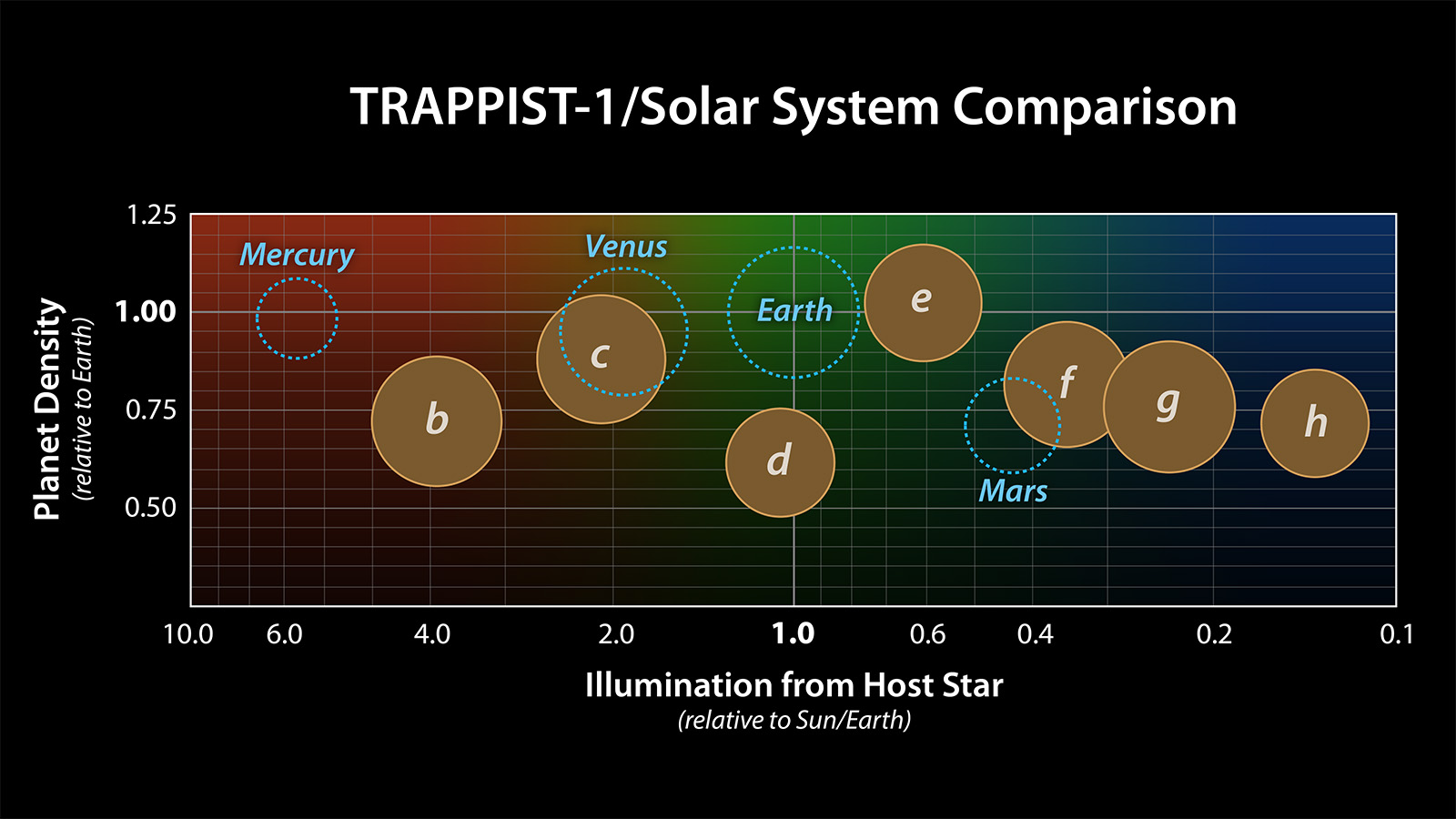

With the announcement of the discovery of seven planets comparable to Earth orbiting the star TRAPPIST-1, our faith in such searches has gotten just a little bit stronger. At least three of them might be at the right temperature to support liquid water and thus the possibility of life as we know it.

Their ongoing search for planets around small, relatively cool stars in our nearby galactic neighborhood uses a pair of robotic telescopes called “TRAPPIST”; the acronym stand for the TRAnsiting Planets and PlanetesImals Small Telescope. TRAPPIST South, which made the observations reported here, is located in the Chilean desert at an observatory in La Silla run by the European Southern Observatory; its counterpart, TRAPPIST North, is located outside of Marrakesh, Morocco. The star TRAPPIST-1 bears the name of the telescope that made it famous.

While most of the excitement in the popular press has centered on the possibility that life could exist on these planets, I see a wider significance to the discovery.

Believing in what you can’t see

It’s important to note that no one has actually seen these planets. They are too small and too faint to be visible in our current generation of telescopes. But even though we can’t see them, we believe they exist because of the effects we can see that they have on their star. This planetary system happens to be aligned so that as each planet orbits this star, it passes between the star and us; thus the starlight is slightly dimmed as the planet passes. Such an effect, though subtle, can be detected even with a small telescope. The TRAPPIST telescopes use very modest 0.6 meter-wide mirrors to capture the flickering starlight.

Since plenty of other things could cause a star to dim, one has to keep looking to see if the effect repeats itself on a regular basis, each time the planet completes an orbit. That’s one reason why the team decided to concentrate their search on dim, red stars. A planet would have to orbit rather close to such a star in order to be warm enough to support life. Close planets orbit more quickly; thus we have many more chances to see them dim the starlight, and each time we see that dimming we are more confident that the planet (or planets, in this case) is really there. What is more, with seven planets it takes a lot of observations to sort out the rhythm of dimmings into seven regular periods. This discovery did not come in one moment of revelation, but only after years of patient observing.

Faith in planets

To further increase our faith that these are really planets, the scientists looked for other effects that such planets would have on the star, such as a subtle shifting of its spectral colors. The small flickers seen in a small telescope led to an international effort involving some of the biggest and most sophisticated instruments at our disposal. Besides the TRAPPIST South telescope, the astronomers relied on data from the NASA’s Spitzer space telescope (which observes in the infrared light that this star mostly radiates) and the European Southern Observatory’s VLT (Very Large Telescope) in Paranal, Chile, whose mirror is more than eight meters wide.

No one astronomer could have made all the observations needed to confirm the result. Science is done by a community of people working together toward a common goal. The European Southern Observatory is itself a consortium of astronomers supported by fifteen European nations, plus Brazil.

Why do we do this?

Astronomy is not stars or planets, but the activity of the people who look at those stars and planets. It is human curiosity, the desire to feed the human soul, that motivates this work. Human longings to know how we fit into this universe, and whether there are other places or even other beings like ourselves, excites our imaginations and keeps us looking patiently, night after night. That passion fuels the faith of the astronomers, giving them the hope they need that their long nights of observing will bear fruit.

Of course, along with passion and faith, scientists are also moved by other appetites… and a sense of humor. The Belgian astronomers who built the TRAPPIST telescopes admit that they chose the name to honor the famous beers made by Belgian Trappists!